August 24, 2020

By Ryan Schwartz, First State Heritage Park and Annie Fenimore, John Dickinson Plantation

August 26, 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which guaranteed and protected women’s constitutional right to vote. Read the remarkable stories below to learn more about suffragists in Delaware who made their mark on history.

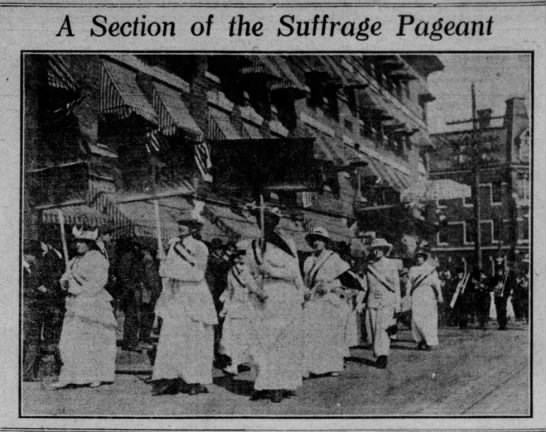

At 3 p.m. on May 14, 1914, a long column of 400 white-clad suffragists marched their way down Wilmington’s Market Street towards Rodney Square. Crowds many times their number lined the boulevard to either side, cheering them on or hissing their dissent by turns. The marchers themselves were a diverse assemblage: men and women, Black and white, young and old, wealthy and poor. Their hands bore banners splashed with color:

White, for the purity of their cause.

Purple, for loyalty, constancy, and purpose.

Gold, for life and the light to guide the way.

Their steps were as steadfast and sure as their resolve: the Woman’s Hour had Struck. Suffrage was coming.

Newspaper photo from The Morning News of the 1914 Wilmington Suffrage March.

Image Courtesy: Newspapers.com

Their movement had begun four generations earlier in 1848 at a now-famous convention held in Seneca Falls, New York. Building off the groundbreaking work of the anti-slavery abolitionists and the anti-liquor temperance societies, suffragists saw their cause as yet another crusade for society’s progression.

Legions of women and their allies participated in the 72-year push to gain the vote, most of whom toiled anonymously in the hope that perhaps their daughters might reap the benefits of their labor. The Wilmington March was the first major public demonstration of the Suffrage Movement in Delaware and the culmination of considerable work by the movement’s leaders in the First State.

The following profiles are just a few of the remarkable Delawareans who made their mark on the history of equal rights, and who are representatives of the many thousands more whose names have been less well-remembered.

The Suffragists & Their Stories

Mary Ann Shadd

1823-1893

Image Courtesy: National Archives of Canada

Mary Ann Shadd was an African American activist, writer, teacher, and lawyer in the years surrounding the American Civil War (1861-1865). She was born to free parents in Wilmington, Delaware, on October 9, 1823, and raised amidst a culture of fervent idealism.

Her parents were both active abolitionists, campaigning for the end of slavery in America. This social activism was no small thing for the Shadd family: Delaware was a slave state with a history of free Blacks being kidnapped and illegally sold into slavery in the Deep South. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 further enacted stiff penalties for those who assisted in the escape of Freedom Seekers; nevertheless, the Shadd family continued to participate in the Underground Railroad, first in Delaware and later in Pennsylvania.

This model of courage set by her parents would inspire Shadd for the rest of her life.

Trained in Pennsylvania as a schoolteacher (since educating African Americans was illegal in Delaware), she subsequently moved to Ontario, Canada. Ontario was the final destination for many Freedom Seekers and was the location of a thriving Free Black population. There, not only did she teach: she made history.

With a headline emblazoned “Devoted to Anti-Slavery, Temperance, and General Literature,” the Provincial Freeman was first published on March 24, 1854. The weekly newspaper was noteworthy for its crusading tone, unyielding stance on moral progressivism, and specific targeting of African Americans as its audience. What made it truly groundbreaking was the publisher behind it: signed, “M.A. Shadd.”

The foundation of the Provincial Freeman propelled Mary Ann Shadd into notoriety within the abolition movement and secured her place in history as the first African American publisher in North America. She lectured widely in Canada and the United States, sharing the stage with abolitionist giants such as Frederick Douglass and met with the soon-to-be-infamous John Brown. To her friends, Shadd was nicknamed “The Rebel.”

In the midst of the American Civil War, Shadd returned to the United States to support the Union cause. Beginning in 1863, she lent her name to the war effort and turned her attention to putting newly-freed Black men into blue uniforms. Thanks to the efforts of Shadd and other leaders like her, nearly 150,000 African Americans would enlist by the war’s end in 1865. Lincoln attributed the fresh manpower and symbolism of African American soldiers returning to the south to purge slavery away as instrumental in winning the Civil War. With slavery abolished, she turned her attention to other causes: public education, the law, and women’s suffrage. While resuming her work as a classroom teacher in the capital’s public schools by day, she undertook courses at Howard University to become a lawyer by night. In 1883—at sixty years of age—she became the second African American woman in US History to earn a law degree.

Likewise, she made her mark on the growing women’s suffrage movement, being invited to speak by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony at the 1878 National Women’s Suffrage Association conference. She subsequently founded the Colored Women’s Progressive Franchise to advocate for equal rights for African American women.

Mary Ann Shadd’s remarkable life came to a close on June 5, 1893, at the age of 69. Her legacy, however, lived on with the marking of her home as a National Historic Landmark in 1976, being designated an honoree for National Women’s History Month in 1987, named a Person of National Historical Significance by the Canadian government in 1994, and being inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1998. In 2018, she was given a belated obituary by the New York Times as a part of the Overlooked Project, which leads with her lifelong philosophy of activism:

“We should do more and talk less.”

Mabel Vernon

1883-1975

Image Courtesy: Library of Congress

Mabel Vernon was an accomplished woman of varied interests and a lifelong champion of causes. Born in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1883, she worked as a teacher until leaping headlong into the struggle for women’s suffrage in 1913. During that first summer, Vernon traveled on a speaking tour through resort towns in New Jersey as well as to locations in Long Island, Rhode Island, and Maryland.

In the fall of the same year, Vernon brought her talents and zeal home to Wilmington. There, she spoke from the street corner of Fifth and Market, which she called “the proverbial place for street-corner meetings.” Rather than standing on the street corner itself, Vernon and her friends inventively utilized the car they had driven into the city as a makeshift platform to deliver a positive message on women’s suffrage. Vernon gained a well-earned reputation as a persuasive orator, with a talent for swaying others to her viewpoint. In fact, on one occasion, she inspired fellow Delawarean Florence Bayard Hilles (see below) to take up the suffrage cause. Hilles would go on to be become a leader in her own right.

The next year, 1914, she set off for the American Southwest, driving to Nevada while stopping regularly to make stump speeches all along the way. Once she reached her destination, she threw herself into lobbying for Nevada’s referendum on women’s suffrage, which was ultimately successful. After attending San Francisco’s Women Voter’s Convention September 1915, she embarked on a four month return to the eastern seaboard.

Once there, Washington D.C. became the new venue for her activities in 1916. On Independence Day that year, she gained notoriety by interrupting a public speech by President Wilson. In her own words:

Yes, there was a great assembly with the President speaking to a crowd. We [Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and I] had gotten tickets from some congressman or someone to admit us to the platform.

As the President was speaking, at the appropriate moment I lifted my voice and said, “Mr. President, if you consider it necessary to forward the interests of all the people, why do you oppose the national suffrage amendment?” And of course, there wasn’t any answer. Then a little while later I said, “Answer, Mr. President.”

The President was very good about that kind of thing. He was very bland; he just went right on as if he hadn’t heard anything. I am sure I spoke in loud tones.

But then, after the first time I spoke, I think, a secret service man made his way to us and said, “Now you mustn’t do this again.” And I said, “I won’t unless it seems necessary.” And then I spoke up again. He took me by the arm and very kindly and gently assisted me down from the platform. I was always amused because the secret service man said to me, “What makes you act this way?”

I went right home to Delaware after the cornerstone laying. When I got there, my mother, who seldom made a remark about what I did, said, “I don’t think that was very polite to the President.” And I made a speech to her on politeness and principle.

She seemed to delight in pushing the envelope. In December that same year, she and another suffragist smuggled a banner into a joint session of Congress that read, “Mr. President, what will you do for woman suffrage?” As the President rose to speak, the banner was unfurled over the balcony railing. Though it was swiftly tugged away from them, the point was well-made. Vernon’s was an ascendant star in the suffrage movement.

By 1917, when the Congressional Union and National Women’s Party merged, Vernon’s fame was such that she became the NWP’s new secretary. In the role, she most famously organized the picketing of the White House: what is today known as the “Silent Sentinel Campaign.” She was also (proudly) among the first to be jailed for her actions: Vernon and six other Delaware women—known as the “Delaware Seven”—were jailed in Occoquan, VA, for refusing to pay a fine for “obstructing traffic.” Following their release, the women were not deterred: they went on tours around the country, garnering support for the women’s suffrage movement by speaking about their treatment in prison.

Vernon’s activism on behalf of women’s equality wasn’t limited to the suffrage amendment. In 1918, she returned to Nevada to campaign for Anne Martin as she sought to become the first woman elected to the U.S. Senate. The two of them were a whirlwind across the state but, in spite of their titanic efforts, Martin did not win the seat. Instead, Hattie Caraway of Arkansas became the first female U.S. Senator beginning in 1932.

Returning to the NWP in 1919, she continued as a regional organizer and was able to celebrate an incredible coup: President Wilson’s endorsement of the suffrage amendment. With his stamp of approval secured, Congress swiftly relented and passed the 19th Amendment on June 4th, 1919, sending it to the states for ratification. Vernon’s tireless work continued, speaking and fundraising through 1920 and the final ratification of the amendment that August.

Mabel Vernon’s story doesn’t end there. In 1924, she earned a master’s degree in Political Science from Columbia University. In the 1930s and 1940s, she set her sights on international relations, involving herself in a variety of organizations, including the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Mabel Vernon died an exceptional, accomplished woman in September of 1975.

Florence Bayard Hilles

1865-1954

Image Courtesy: Library of Congress

Florence Bayard Hilles was born into Delaware’s politically influential Bayard family in 1865. Her early life as a well-connected and wealthy woman was unremarkable, apart from her family’s brief stay in England while her father served as the U.S. Ambassador (and where she herself was formally presented to Queen Victoria!); that all changed in 1913 thanks to one woman: Mabel Vernon.

While attending the Delaware State Fair, she happened to hear Vernon speak on women’s right to vote. Inspired, she left a card stating, “I believe in woman suffrage,” and later went onto remark that “Mrs. Vernon is saying what I believe in and I’m not doing anything about it.” Hilles would remedy that by committing herself to the battle for the ballot.

Within the year, she had asserted herself as a leader in the Delaware movement. She was instrumental in organizing the 1914 Suffrage March in Wilmington (referenced at top), timed to coincide with other such demonstrations across the country. Barely a week later, she was marching herself in Washington, D.C.

One of the strategies suffragists adopted was to pursue the ballot box through individual states. To that end, Hilles turned her efforts to an Equal Suffrage Amendment for the Delaware State Constitution. In a stroke of imagination, she turned her car into the “Votes for Women Flyer” and toured the state for two months in 1915, using her back seat as a platform in small towns across the First State. The next year, she took “The Flyer” nationwide on a tour that ended in Seattle, Washington, where she promptly rented a plane and used it to scatter pro-suffrage pamphlets across the city!

The very next year, the United States entered World War I and suffragists like Hilles received harsh criticism from their opponents, who claimed that they put the suffrage cause before their patriotic duty to support the war effort. Even members of her own family, scandalized by her activities, leveled this charge against her personally. To prove them wrong, she promptly took a job at the local munitions factory, demonstrating that supporting the suffrage cause and her country were not incompatible goals. She and other munitions workers would even seek out an audience with President Wilson to argue that, just as soldiers risked their lives for their country in the trenches of Europe, so too did they in the dangerous armaments factories; did they not deserve the same vote? Their request for an audience, however, was refused.

In July 1917, Hilles took part in one of the most effective and controversial tactics of the suffrage movement: the “Silent Sentinel” campaign, organized in-part by her friend Mabel Vernon. Hilles subsequently became among the first to picket the White House itself. In response, she and 15 other women were arrested on flimsy charges of “obstructing traffic” and ordered to pay a $25.00 fine. Hilles and every one of her compatriots steadfastly refused and were instead given 60-day terms at the infamous Occoquan Prison; they were, however, pardoned by President Wilson after just three days. Though his personal reasons have never been made public, historians speculate that he was either appalled at the treatment of previously-sentenced suffragists or simply wished to avoid more bad publicity.

Following her imprisonment, Hilles was quoted in an article stating, “What a spectacle it must be to the thinking people of this country to see us urged to go to war for democracy in a foreign land, and to see women thrown into prison who plead the same cause at home!”

In 1919, Congress passed the 19th Amendment and President Wilson signed it. Then, it required the ratification of 36 states to go into effect. The fight for ratification came to Delaware in 1920, where the state had the opportunity to make the 19th Amendment the law of the land. Hilles joined other suffragists leaders in speaking before the Delaware General Assembly. As the special legislative session continued, it was obvious that the margin would be razor-thin and both the “Suffs” and the “Antis” were forced to adopt unorthodox measures to win over legislators to their cause. Perhaps the most famous incident surrounded an attempt by suffragists to delay a vote they feared would go against them. To buy time, Hilles and a few compatriots essentially abducted the committee chairman, driving away with Representative Hart in Hilles’ trusty automobile and so delaying the vote. Though critics cried foul, suffragists maintained that Hart entered the car of his own free will and Hart himself later issued a statement denying that he had been kidnapped.

Despite the fantastic lengths Hilles and her fellows went to, in the end, the Delaware House of Representatives refused to vote on ratification of the 19th Amendment. No doubt disappointed, Hilles followed the movement to Tennessee, where the state legislature ratified the amendment by a thin margin in August of 1920.

Following her role in the women’s suffrage movement, Florence Bayard Hilles went on to indulge in a variety of interests, including golf and gardening. She served as the NWP’s chairwoman in the 1930s. She also advocated for the as-yet unadopted Equal Rights Amendment. In Washington, D.C., the Sewall-Belmont House Museum’s library is named after her: the Florence Bayard Hilles Research Library.

After a long, dynamic life, Hilles died in 1954, an icon of her cause. Nowhere is this expressed more clearly than by fellow national suffrage movement leader Alice Paul, who wrote to Florence Bayard Hilles in 1941, “I take you as my model and try to be as gallant and generous and courageous as you are. I could wish for nothing more.”

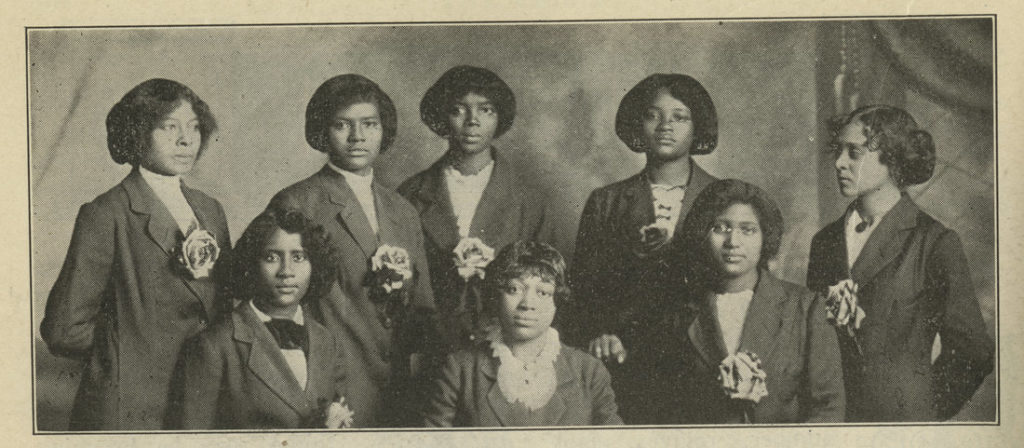

Alice Dunbar-Nelson

1875-1935

Image Courtesy: University of Delaware Library

Alice Dunbar-Nelson was born in 1875 as Alice Ruth Moore in New Orleans, Louisiana. An educator, poet, and activist, she overcame considerable discrimination throughout her life: due to her light complexion, she was simultaneously too Black for some and not enough so for others. Nevertheless, she persisted and became one of the most remarkable and influential African American women of her generation, the first to be born free following the American Civil War.

After a tumultuous childhood, Dunbar-Nelson pursued and received a teaching certificate from Straight College in New Orleans. Faced with overwhelming obstacles to pursuing her chosen career in Louisiana, she initially set her eyes on New York City and settled in Brooklyn. Her stay there would be short-lived, moving to Washington, D.C. during a brief and tumultuous four-year marriage, and then to Wilmington, Delaware, where she taught at the segregated Howard High School beginning in 1902. Once again facing opposition from all sides, she later recollected, “It was only sheer grit and determination not to be beaten that kept me from throwing up the job and going back home.”

Alice Dunbar-Nelson was truly nothing if not determined. She first became a published poet and author in 1895 with her first book, Violets and Other Tales. She published another book only four years later, titled The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories. In addition to her short stories and poems, Dunbar-Nelson worked as a journalist, wrote and published essays, and even a play. During her lifetime, Dunbar-Nelson’s work was popular, but critics’ remarks were more often about the author—both her complexion and education—rather than her work. Today, scholars recognize the valuable contributions her writing made to the Harlem Renaissance for its content and form.

Her civil rights activism began in 1912, when she began serving as the secretary for the Wilmington Branch of the NAACP. Along with other leading African American suffragists Blanche Williams Stubbs, Mary J. Woodlen, and Alice Gertrude Baldwin, Dunbar-Nelson organized the Equal Suffrage Study Club two years later.

By 1915, Dunbar-Nelson was wholly immersed in the suffrage movement. She became a field organizer in the Mid-Atlantic States, notably traveling through Pennsylvania to encourage support of a state referendum on women’s suffrage. Though the referendum failed, she was praised in newspaper articles for her oratory skills.

In July 1916, she attended the Delaware Congressional Union’s convention as a representative for the Garrett Settlement House, a community center for African Americans. Two years later, in the midst of World War I, she toured the south as a field representative of the Woman’s Committee of the Council of National Defense; in this capacity, she returned reports determining how to incorporate and mobilize Black women and created pragmatic state-by-state strategies for either integrated or segregated organizations.

Congress passed the 19th Amendment and by March of 1920, 35 states had ratified it, requiring only one more for it to go into effect. Joined by Florence Bayard Hilles (highlighted above) Alice Dunbar-Nelson addressed groups of African American suffragists in Delaware in April of 1920, just weeks before the legislature’ special session to debate the amendment. Despite a large pro-women’s suffrage rally in Dover later that month and much pressure from suffragists and their political allies, the Delaware Legislature did not ratify the 19th Amendment. Tennessee ratified the Amendment two months later, thus finally making it part of the United States Constitution.

After the 19th Amendment passed, Alice Dunbar-Nelson continued to organize for African American rights. Beginning in 1922, she took a leadership role in the Delaware section of the Anti-Lynching Crusaders, a social movement led by Black women to fight for the passage of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. She also worked as a teacher and parole officer at the Industrial School for Colored Girls from 1924 to 1928. From 1928 to 1931, she traveled and engaged in more public speaking, this time for the American Friends Inter-Racial Peace Committee.

In addition to the litany of organizations and causes in which she was involved, Alice Dunbar-Nelson continued to write and publish poems and articles. During this decade, she also kept a diary. In it, she describes romantic liaisons with women while remaining married to husband Robert Nelson, which many scholars have cited as evidence of her bisexuality. Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s diary remained private during her lifetime but now survives at the University of Delaware’s collection.

In 1932, Alice Dunbar-Nelson followed her husband and longest-lasting romantic partner, Robert Nelson, to Philadelphia when he was appointed to the Pennsylvania Athletic Commission. Her health continued to deteriorate following the move.

Alice Dunbar-Nelson, aged 60, succumbed to a heart ailment s in 1935. After her cremation, Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s ashes were scattered in the Delaware River. She once wrote a poem about the Delaware River, which was published posthumously. This is the first stanza of that poem:

“O white little lights at Carney’s Point,

You shine so clear o’er the Delaware;

When the moon rides high in the silver sky,

Then you gleam, white gems on the Delaware.

Diamond circlet on a full white throat,

You laugh your rays on a questioning boat;

Is it peace you dream in your flashing gleam,

O’er the quiet flow of the Delaware?”

Remembering the Suffragists 100 Years Later

August 26, 2020, marks a century since women won the vote. The efforts of the remarkable women above and thousands more like them secured the 19th Amendment to the United State Constitution, one of the great landmark expansions of civil and social equality in American history. As a result, 26 million women were enfranchised in time for the national election that November; today, the number of eligible female voters is over 100 million. Though it took time for them to make their presence felt in the electoral process, according to the Pew Research Center, they have consistently turned out to vote at slightly higher rates than men in every presidential election since 1984. The suffragists would be proud.

It is worth remembering, however, that the 19th Amendment’s passage was not the end; rather it was another leap forward toward a larger promise of equality.

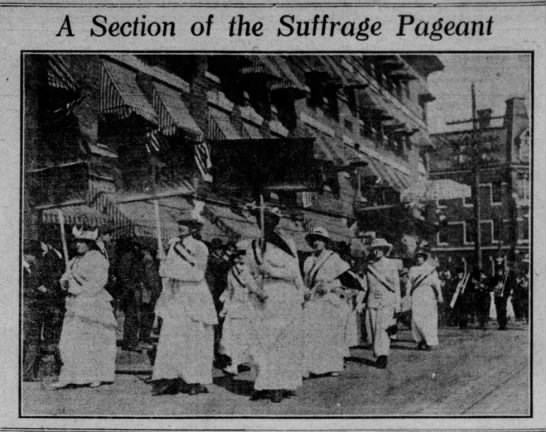

Unknown African American Suffragists

Image Courtesy: The Gotham Center for New York History

Although the 19th Amendment barred voting discrimination based on sex, the serious impediments for people of color in general, and often women in particular, remained to be conquered:

-

-

- Native Americans were not made citizens until 1924, and a number of states continued to bar their access to the ballot box until 1957.

- Poll taxes and literacy tests kept many immigrants and poor people from voting, a practice that especially impacted LatinX peoples. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 and its subsequent expansion in 1975 to include bilingual ballots were major victories for that community.

- For Asian-Americans, the primary impediment was the antiquated Naturalization Act of 1790, which made citizenship for newly-arrived immigrants virtually impossible under the claim that they were not “free white citizens” as the Act demanded, although children born on American soil were granted citizenship status. The remnants of the 1790 Act would not be purged until 1952.

- Because of Jim Crow, African American women—so active in the suffrage movement of the early 20th century— would not receive full access to suffrage until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

-

Mabel Vernon and other suffragists watch another star stitched in, representing another state in favor of ratifying the 19th Amendment.

Image Courtesy: Library of Congress

The passage of the 19th Amendment was an undeniable victory: it not only secured the legal foundation for women suffrage, but for expanded suffrage to those previously denied it across the nation. It was an inspiring act that brought the United States closer to the fulfillment of the promises of liberty and equality that lie at the heart its founding. Just as their forbearers had, the suffragists who won the ballot box in 1920 perceived injustice and threw themselves into correcting it, out of a desire to create a “more perfect Union.” Subsequent generations have since been inspired to do the same.

From the very earliest days of human civilization on this continent, women have played an instrumental role, one that has tragically often been lost to the sands of time. As we commemorate the Centennial of Women’s Suffrage, we can look back with pride at the works of redoubtable women like Mary Ann Shadd, Mabel Vernon, Florence Bayard Hilles, and Alice Dunbar-Nelson, and upon the labors of those stirred to action by them.

Perhaps the best testament we can leave the “Silent Sentinels” and “Iron-Jawed Angels” who crusaded for equal suffrage 100 years ago is to commit ourselves anew to the elevation of the underserved stories of history, and to carry on their principles: that safe and free access to the ballot box is the right of all citizens, and that only through achieving that lofty ideal can we ensure the flourishing of democracy both in the country at-large and in its First State.