September 17, 2020

By Tyler Dreiblatt, Interpretive Programs Manager at Cape Henlopen State Park

All photographs courtesy of the Delaware State Parks Cultural Resources Unit

Cape Henlopen’s Strategic Location

Cape Henlopen has been an important strategic location since before our country was founded. In 1775, a lighthouse located at the cape was designated Station Number 1 by the patriot-aligned Pennsylvania Committee for Safety, responsible for alerting continental forces to any British ships entering the Delaware River. A year later a small patriot militia fended off the British warship HMS Roebuck, while in 1813 the town of Lewes was bombarded by the British HMS Poiciters. During the First World War, the Army constructed experimental firing platforms at the cape, and in 1938 artillery practice was conducted at “Camp Henlopen.” But as the clouds of war gathered during the 1930s, U.S. military planners began to worry about serious enemy attacks against the Delaware Bay and River. Shipyards, oil refineries, arsenals, machine works, and more dotted the banks of the river, all in need of defense. The Army decided that a new, powerful defensive installation was needed at the cape.

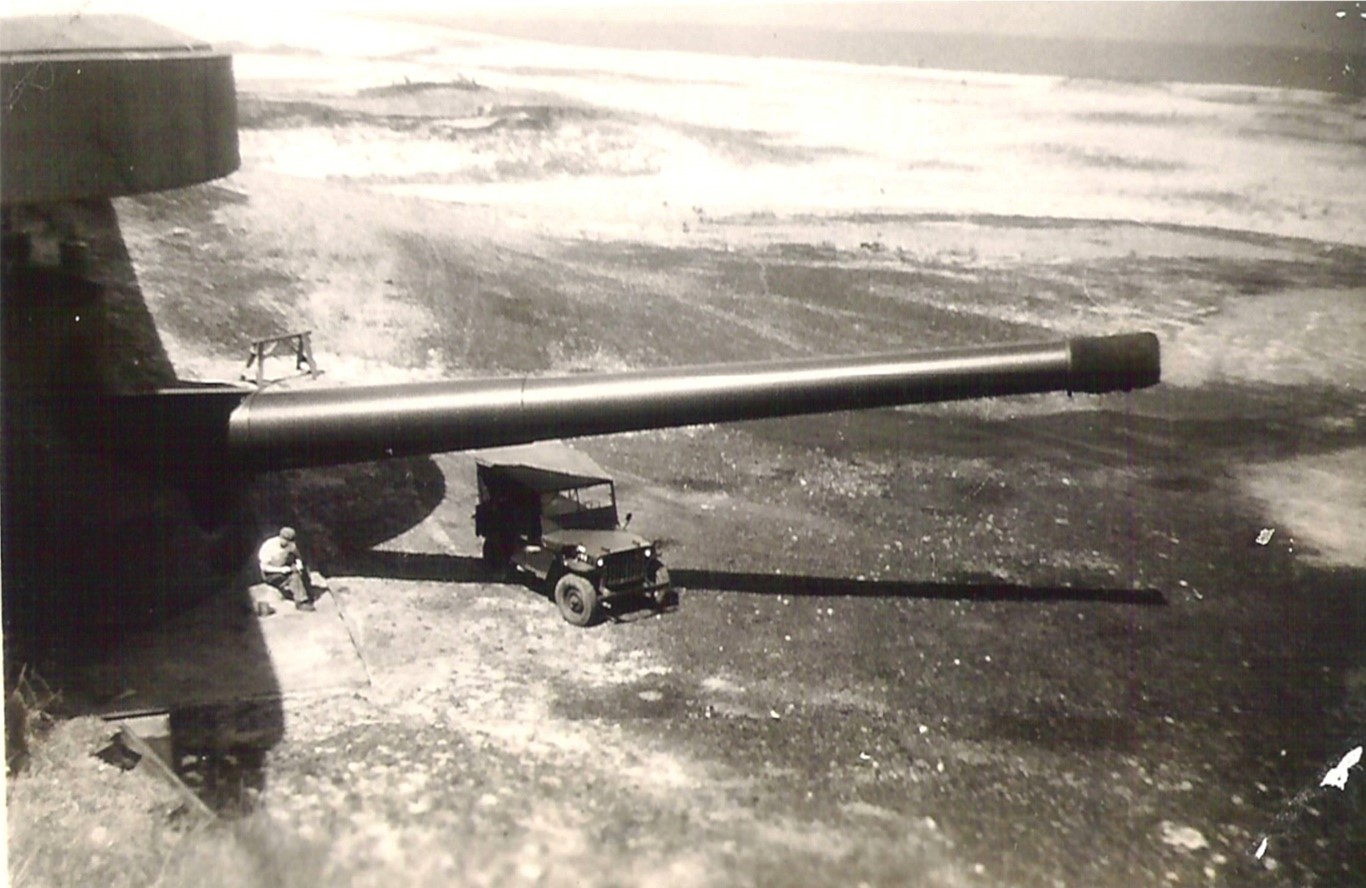

Artillery practice at Cape Henlopen, 1938

Army engineers began surveying the area in the summer of 1940. Construction of the first fortifications began in March of 1941, and the first garrison – consisting of Battery “C” of the 261st Coast Artillery – was established a month later. In August of 1941, the base was officially named Fort Miles. A hospital, gymnasium, administrative buildings, and permanent barracks sprung up over the next few years. Eventually, the fort would contain over 2,000 people, cover over 1000 acres, and cost $22 million to build.

Battleship Defense

Prior to the outbreak of World War II, U.S. military planners were primarily concerned with defending against large battleships like the German Bismarck and Tirpitz. This is reflected in Fort Miles’ armament. 12 batteries of guns operated at Fort Miles at various times, including 3-inch and 90-millimeter anti-air/anti-motor torpedo boat guns, 155-millimeter, and 6-inch gap-filler guns, 8-inch railway guns, and 12-inch and 16-inch anti-battleship guns. A total of 15 Fire Control Towers (11 in Delaware and 4 on Cape May) were erected to spot enemy ships. This system was meant to provide a layered defense against enemy warships, at a maximum range of 25 miles. Ultimately, however, the threat of surface ship attack failed to materialize.

One of the 16-inch guns of Fort Miles

World War II Defense

As the war progressed, the true danger emerged: German U-boats or submarines. U-boats lurked offshore, attacking coastal shipping and transatlantic convoys. Unfortunately, the guns at Fort Miles were not designed to engage submarines, and sub-hunting was left to the Navy. The men of Fort Miles were responsible, though, for keeping enemy submarines out of the Delaware Bay and River. In October of 1941, a joint Army-Navy Harbor Entrance Command Post was established to coordinate the sea-based defense of the bay. In April of 1942, two magnetic loop coils were placed in the waters around the cape. The loop coils were triggered by any large, metallic object that passed over them, providing an early warning signal to the fort. Three to four sonar buoys were placed in the bay to aid in submarine detection, and an anti-submarine net and boom were briefly installed up-river.

Additionally, 455 sea mines were planted across the entrance to the bay, organized into 35 groups of 13 mines each. Mining operations were centered around what is now the fishing pier and involved hundreds of personnel. Each mine was wired into control boards in the fort, allowing remote detonation. The placement and maintenance of the minefield and related equipment became one of the major tasks at Fort Miles and could be hazardous (especially in bad weather).

Surrender of U-858

The biggest action Fort Miles saw was the surrender of U-858. Dispatched to the coast of North America near the end of the war in Europe, U-858 surrendered to ships of the Atlantic Fleet on May 9th, 1945. An American prize crew was put aboard, and the submarine was escorted to Cape May, New Jersey. 37 of the 56-man crew were taken by ship to Fort Miles, while the rest- accompanied by the prize crew- piloted the U-boat into the harbor of refuge at Cape Henlopen. The crew was briefly interned at the fort before being sent to various prisoner of war camps, while the submarine was eventually taken to the League Island Navy Yard in Philadelphia for research.

The crew of U-858 waiting to be interned at Fort Miles, 1945

After World War II

On September 2nd, 1945, World War II ended. Activity at Fort Miles, however, did not. That same year, the Navy contracted the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab to design a long-range, ship-fired missile to be used against aerial targets. Initial testing was done at Island Beach, a remote community in New Jersey. It soon became clear, however, that there were too many ships operating in the area. Testing at Island Beach was unsafe.

In December 1945, Bumblebee equipment began shifting to Fort Miles. The area around Cape Henlopen offered more room for testing the new technology. New research and repair buildings were raised near Battery Herring while tracking equipment was attached to the battery and some of the World War II-era fire-control towers. Rockets were test-fired over the ocean from the beaches east and south of Herring Point. Over thirteen months, dozens of test flights were carried out at Fort Miles. Eventually, however, the problems from Island Beach reappeared. There was too much activity in the area for secret missile tests. In March 1947, Operation Bumblebee was relocated to Topsail Island, North Carolina.

One interesting footnote to Bumblebee’s time at Fort Miles comes to us from Horace Wenyon. Mr. Wenyon was a civilian pilot who flew around the Cape region. One September day in 1946, Mr. Wenyon was out flying his plane over the ocean near Rehoboth Beach when he spotted an object he couldn’t quite make out streaking up into the sky, moving fast and trailing flame. A month later, the same thing happened. On June 2, 1947, he saw it again. Mr. Wenyon reported each sighting to the FBI. Eventually, his reports made their way to the Air Force, which was studying possible extraterrestrial sightings under the codename Project Bluebook. Mr. Wenyon never claimed he had spotted an extraterrestrial craft; just something he couldn’t identify. He suggested a rocket, which is the same conclusion the Bluebook investigators came to. The three objects Mr. Wenyon saw were officially declared to have been Bumblebee rockets test-fired from Fort Miles. The only problem is, Bumblebee testing at Fort Miles had ended three months before the last sighting was reported. So did Mr. Wenyon get the date wrong, or did he see something unexplained? Hopefully, further research can solve this mystery.

A Bumblebee missile test at Fort Miles, 1946-7

Missiles at Fort Miles

Missiles quickly became a powerful part of the United States anti-aircraft defenses. Prior to the 1950s, missile batteries operated independently of one another. As the Cold War intensified, the Army felt a more unified system was needed. To better coordinate these independent defenses, the Army began the Missile Master program. Missile Master used large radar and communication networks to detect possible threats and assign missile batteries to counter those threats. Most of the equipment was centralized, with radar towers right next to the buildings where Missile Master personnel operated. Much like cell towers, however, radar sites can have “dead zones” that their signal does not cover. These “dead zones” were a potential defense issue, so the Army set up smaller “gap-filler” radar sites to increase radar coverage. One of those “gap-filler” sites was located at Fort Miles.

By 1959 a radar dish had been installed on top of Battery 519, a World War II-era gun emplacement, and Missile Master personnel were hard at work inside the battery. Originally built to fight German battleships, Fort Miles was now scanning the skies for Soviet bombers. The fort was no longer expected to fire guns at the enemy but still contributed to the defense of the nation through this “gap-filler” site. The Missile Master system ended in the 1970s, and the radar dish was removed from Battery 519.

The National Emergency Command Post Afloat

As Missile Master watched the skies, government planners were wondering: what happens if an enemy bomber gets through? Bunkers were built to keep the President and other officials safe, and plans were made for their evacuation. One of these plans was known as “NECPA:” the National Emergency Command Post Afloat. Beginning in 1962, two ships – the USS Northampton and the USS Wright – were essentially turned into floating Pentagons. They could be sealed against a nuclear blast and could communicate with almost any location in the world. This long-range communication was made possible by tropospheric scatter transmitters. These large antennae bounced high-powered signals off the troposphere (a layer of the atmosphere), creating a secure and reliable message. In 1964 the Navy placed tropospheric scatter antennae on top of Battery 519 to better communicate with the Wright and Northampton. At 120 feet tall, the antennae dominated the landscape until 1970 when the NECPA program ended.

Tropospheric antennae on top of Battery 519, 1969

Submarines and Fort Miles

Bomber aircraft was just one threat during the Cold War. The United States military was also worried about Soviet submarines. It was now possible for enemy submarines to launch missiles at American targets from miles away. To combat this threat, the Navy developed the Sound Surveillance System, known as SOSUS. SOSUS was a collection of underwater microphones placed in a layer of the ocean that carries sound very well. These microphones fed into shore-based naval facilities where personnel could analyze the sounds that were picked up. With advanced training, these sailors could locate and track enemy submarines.

Originally, 11 facilities (also known as “NavFacs”) made up the SOSUS program. One was NavFac Cape May, located just across the bay from Fort Miles. NavFac Cape May was established in 1955, but by 1960 the Navy realized Cape May was not an ideal location. The beach around the facility was rapidly eroding, so the decision was made to relocate to Cape Henlopen. The Army transferred 614 acres at the south of Fort Miles to the Navy for the construction of NavFac Lewes. To support NavFac Lewes, the Navy built a two-story multipurpose building with offices, a kitchen, and living spaces. This building still exists as the Biden Center. Battery Smith, a World War II-era gun battery, was turned into storage, support, and recreation space. Another gun battery, Battery Herring, was used for signal processing.

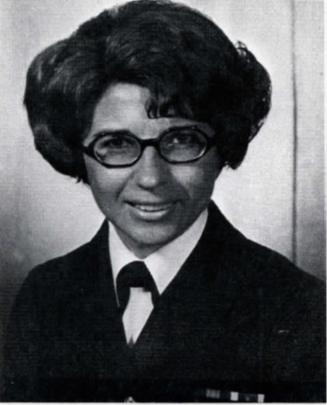

NavFac Lewes closed in 1981. During its time of operations, the facility received a Naval Unit Citation, two Meritorious Unit Citations, and won the Navy Excellence “E” Award three years in a row. In 1977, NavFac Lewes became the first SOSUS facility with a female commander when Lt. Cmdr. Margaret Frederick was assigned to the base.

Lt. Cmdr. Margaret Frederick, 1977

Fort Miles as a Vacation Spot

Fort Miles had a fun side as well. Beginning in the 1960s, parts of the fort were used as military morale, wellness, and recreation areas. These were basically military-run vacation spots for families in the armed services. The area around Battery 519 was used by the Army, while the Air Force had its own section near what is now the Hawk Watch. The Fort Miles Recreation Area was a popular destination for soldiers, sailors, and airmen stationed near the mid-Atlantic until 1991 when the program ended.

Fort Miles Today

By 1996 all Fort Miles land at Cape Henlopen had been incorporated into Cape Henlopen State Park. Although the fort never saw combat, the men and women who served at the cape did so with honor and distinction. Today, State Park staff and the Fort Miles Historical Association work together to preserve and share their stories.