February 24, 2020

By: Kenneth Horowitz, Interpreter at Delaware Seashore State Park

The Indian River Inlet, located in Delaware Seashore State Park, is the connection between the Indian River and the Atlantic Ocean. Throughout its history, this dynamic waterway has played a major role in the development of the Delaware coast. By connecting the Indian River Bay and Rehoboth Bay with the Atlantic ocean, the inlet provides an entry point (and the salinity) that crabs, oysters, horseshoe crabs, and many fish species need to survive in the bays. The inlet has also allowed shipping traffic in and out of the inland bays for much of its history.

There are many inlets like this along the coast of the Delmarva peninsula, and over time these inlets have been subject to dramatic change. Many of the inlets move over time. The inlet where Lewes Creek empties into the Delaware Bay had moved from somewhere near Lewes in the 1600s to several miles northwest by 1937 when the new Roosevelt Inlet was opened closer to town. This is a natural process called littoral drift, where sand is carried by a current and deposited further along the current’s path. However, some inlets closed entirely – the Sinepuxent Inlet closed in 1819 along today’s Assateague Island and never re-opened. Like most things along the coast, inlets – and inlet locations – are only temporary arrangements.

1801 “A Map of the State of Delaware and the Eastern Shore of Maryland,” Indian River Inlet is labeled “False Cape.”

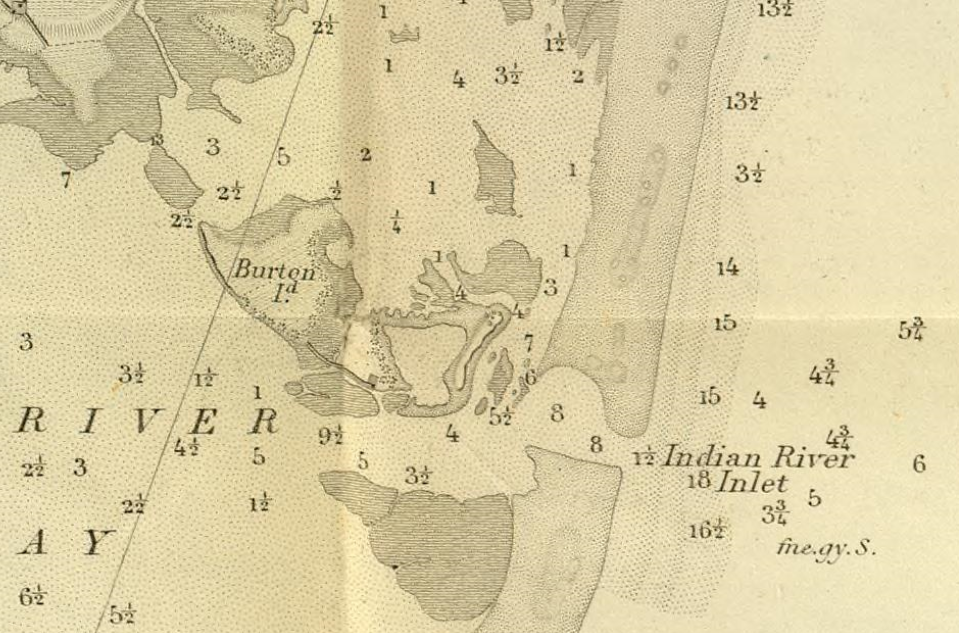

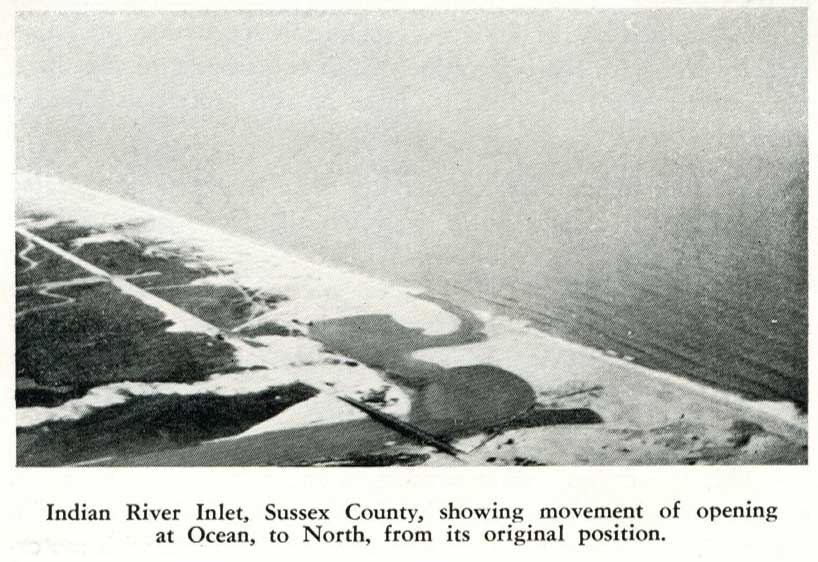

The Indian River Inlet was no different. From its early 1800s location near the south of the Indian River Bay, it gradually moved north over time. By 1848, it was just south of Burton Island. However, as it moved north from there, becoming parallel with Cedar Island, it began to shoal more and more. By 1880 at least, it had developed a large shoal, nicknamed “the Bulkhead” by locals, that became a hazard for navigation.

1848 “US Coast Survey of the Delaware Bay, River,” close-up of the Indian River Inlet.

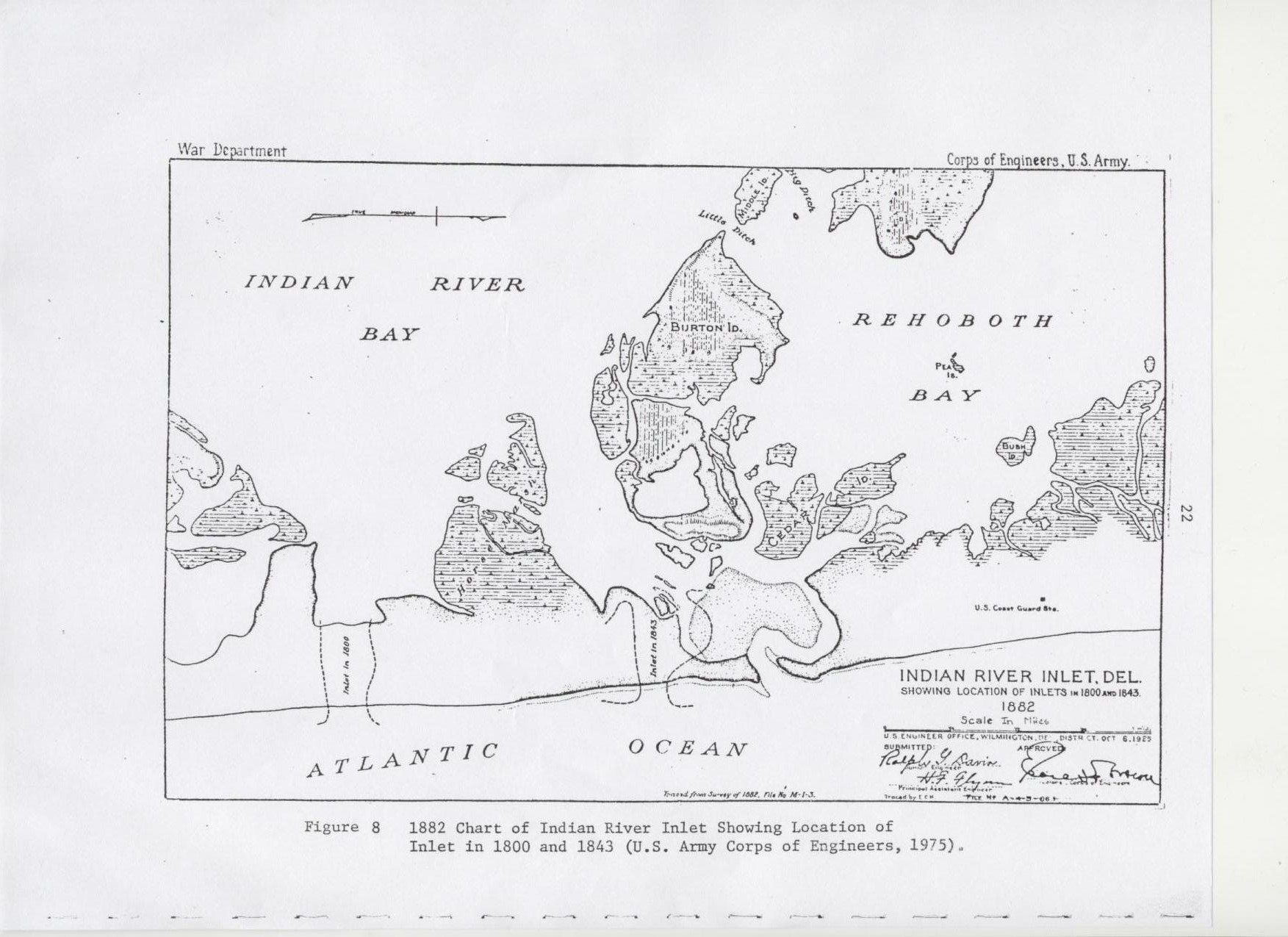

In 1882, the Army sent out engineers to survey the inlet and come up with a solution. They proposed dredging a channel to the inlet to allow shipping traffic to continue. Some dredging was done in the following years, but the project was abandoned by 1887 and the shoaling continued. By 1908, the problem was so bad that 300 people worked for 3 days to dig open a new inlet at its estimated 1800 location. The new inlet did not last long, and the old inlet re-opened soon after. By 1911, the inlet had almost closed completely until a storm in February 1912 re-opened it. But in 1915, the inlet closed entirely. It re-opened naturally within a few months, but it was clear that the inlet would not last much longer on its own.

Park photo collection – 1882 “Chart of Indian River Inlet,” created by the US Army Engineers. The “Bulkhead” shoal is the shaded space in the inlet.

The Army engineers did a study in 1916 and found that the cost of opening the inlet to help shipping would have been very, very high to help a small shipping fleet of only 18 or so ships. Delawareans decided to tackle the problem on their own – in March 1918, 200 people set out to re-open the inlet. Armed only with shovels, they worked for two days to dig the struggling inlet to a navigable depth, only for a storm to wipe out their hard work a few weeks later. Another storm reversed the work of the first, and actually opened the inlet so wide that a whale swam into the inlet, giving local fishermen quite a fright! However, by winter, the inlet had badly shoaled or closed again entirely.

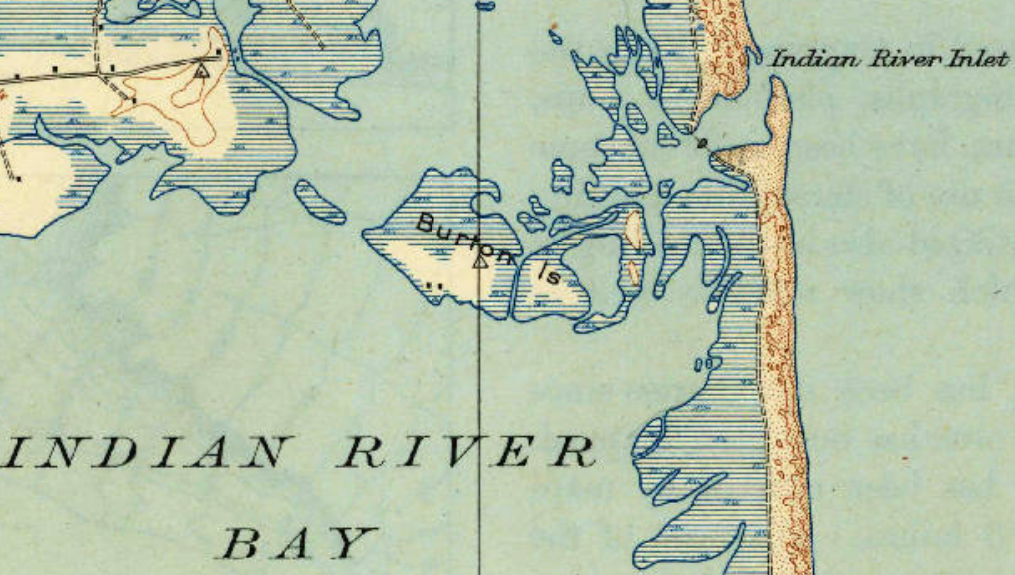

1918, “US Geological Survey,” showing the Indian River Inlet at its northernmost location.

In early 1919, Delaware’s General Assembly created an Indian River Inlet Commission to investigate opening the inlet once more. While the commission argued amongst themselves about where to put it, Sussex County farmers solved the location problem for them with a copious amount of dynamite, blasting open the inlet at its 1918 location. This inlet, just like the last one, proceeded to close almost immediately. Another set of Army engineers arrived in March 1920 to inspect the closed inlet, only to find it open again – mission accomplished, they turned for home and left. Soon after it closed once more, prompting the inlet commission to contract a dredging operation for it; when the dredge arrived in 1921, the inlet was open again.

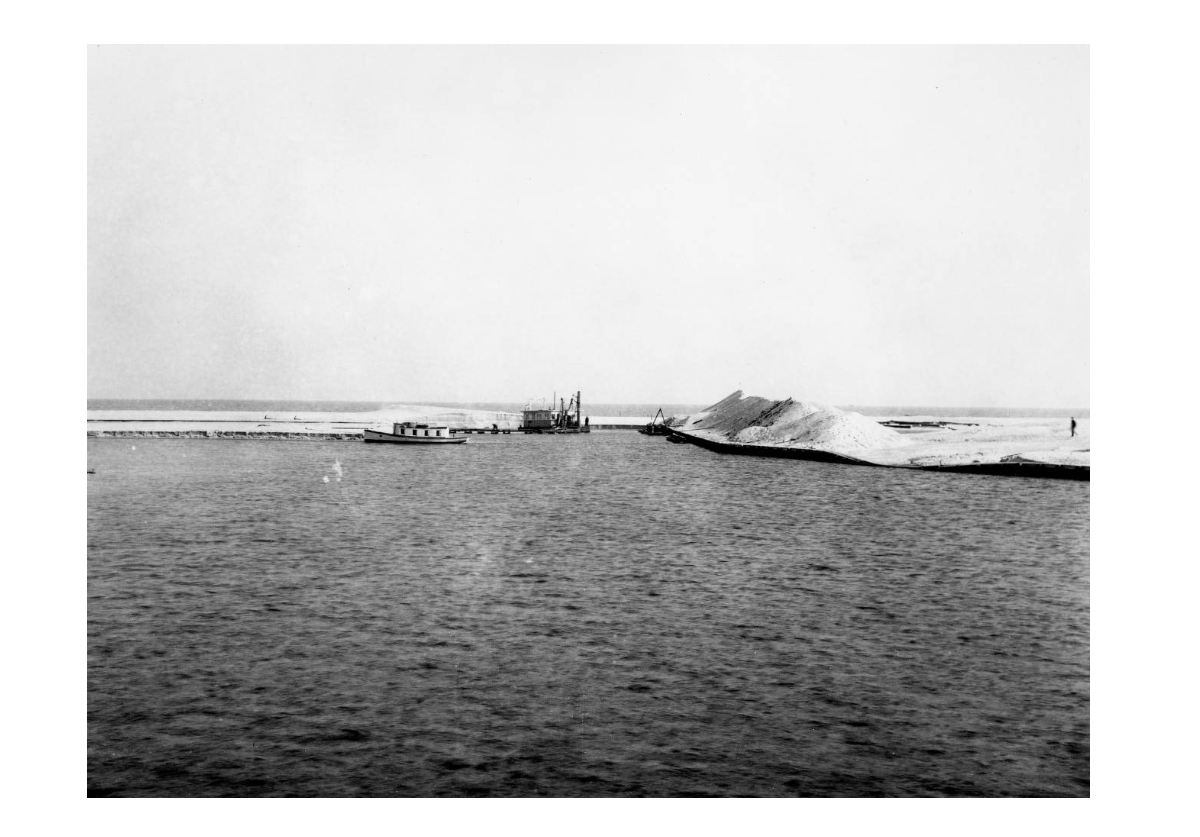

This state of affairs continued until 1925 when the inlet closed and failed to re-open at all. By November 1927, the inlet commission had managed to persuade the Army engineers to return to open the inlet by pointing out that the reduced salinity was destroying the seafood industry in the bays. Exactly one year later, they had dredged a channel for a new inlet at its modern-day location south of Burton Island. The last 100 feet was removed with 2,200lbs of dynamite at 4pm on November 3rd, 1928. Today’s man-made inlet had been created. Not one week later, a storm blew through that shoaled in the new inlet.

Park photo collection – the short-lived inlet of ’28.

In April 1929, another volunteer group assembled to dig out the inlet by hand. They received assistance from Governor C. Douglass Buck, who secured an excavator and its operator for their mission. By May, the inlet was open again; as luck would have it, a big storm right as they finished digging opened the inlet even more. It seemed they finally had their inlet, at long last.

Park photo collection – cruising through the inlet, sometime after May 1929.

Shoaling was still an issue with the inlet, and it had a propensity to follow its original path north over time, just as it had for decades before. This called for dredging every few years to return the inlet to its desired state. The inlet was dredged in 1929, 1931, 1933, and 1935 – sometimes, just barely before it could close again entirely.

DE Public Archives photo – dredging the inlet, sometime in ’31 or ’33.

Park photo collection – the inlet in 1931, following its natural course closer to the ocean.

In 1931, responsibility for the inlet’s upkeep went to the State Highway Commission. Their main mission in the area had been to build a road from Rehoboth Beach to Bethany Beach, connecting the resort towns of Delaware’s coast. In 1933, they built the first “Ocean Highway” along with a wooden bridge over the inlet.

DelDOT photo archives – aerial photo of the new bridge in 1933.

Constant dredging meant constantly paying for dredging – an unappealing prospect, to say the least. The department also had to protect its new Ocean Highway, and a constantly moving inlet posed a threat. The Army engineers were consulted again in 1936, and they recommended adding jetties to fix the inlet in place. A new swing bridge was to be built to facilitate ship traffic as well. The project began in February 1938 and wrapped up on December 9th, 1938, when the inlet was declared officially open. The swing bridge, the second bridge to span the inlet and the first to be called the Charles W. Cullen Bridge, was opened in early 1939, and the wooden bridge removed.

The original jetties were sheet metal with stone in places; today’s modern jetties are reinforced versions of the old ones. Today, the Indian River Inlet is at the center of Delaware Seashore State Park – both physically and culturally. Without the inlet, there would have been no inland shipping, no salt-water fish species or crabs in the bays, and no life-saving station built – the Indian River Life-Saving Station is the only Delaware station surviving in its original location.

Indian River Inlet Bridge Project //DelDOT / 10-31-2008

Credit photograph by Eric Crossan.com

302-378-1700

Aerial view of Indian River Inlet in 2013.

The research used in this article makes up just a part of Delaware Seashore State Park’s new program, “Driving Through Hidden History.” Our park is filled with many more little-known stories – consider signing up for a tour this spring or summer and come learn more of the park’s hidden history!