June 29, 2020

By: Jacque Williamson, Curator of Education & Conservation at Brandywine Zoo

Since 2014, the Brandywine Zoo has been installing and monitoring American Kestrel nest boxes across Delaware. Kestrels (Falco sparverius) are the smallest species of falcon in North America, and one of the smallest raptors. This species relies on vacant cavities left behind by woodpeckers, squirrels, or general decay in old or dead trees. Unfortunately, their population has been in decline across the continent since the 1960s, and no one knows why. Because of their habit of cavity-nesting, they will readily take to man-made nest boxes, making it easier for zoo staff to study them when they choose to take up residence each nesting season.

Kestrels are in decline all across North America, but the cause has eluded researchers. Pesticide accumulation, competition from invasive species, loss of appropriate nesting and hunting habitat, a decline in critical prey base, new diseases, or even climate change are all possible culprits. What we do know is that Kestrels need wide open spaces with mixed height species vegetation that supports their favorite foods: large grasshoppers, rodents, songbirds, and even small reptiles and amphibians. They also need tall places to perch, such as power poles or dead trees, from which they can hunt and cavities for nesting. The grasslands that Kestrels rely on are in decline across North America, under threat from development, degradation, or chemical accumulation.

In Delaware, the American Kestrel is listed as an Endangered Species. Researchers from the Brandywine Zoo have been monitoring their population in hopes of discovering a cause for their declines and hopefully, one day, help determine a path to recovery for them through land management practices and best practices recommendations.

It’s currently nesting season for American Kestrels, and this means it is prime time to band birds while they’re in their nest boxes. When the COVID-19 pandemic started, the Brandywine Zoo had conversations amongst volunteers and staff monitoring nest boxes, as well as landowners, on how to proceed with the banding season. Luckily, fieldwork is inherently isolated – only one person is needed to check a box for nesting activity, and there’s no risk of contamination to birds (coronavirus is affecting mammals, not birds or other taxa at this time). This means that, with landowner permission, the Brandywine Zoo has been able to keep monitoring boxes for Kestrel nesting activities.

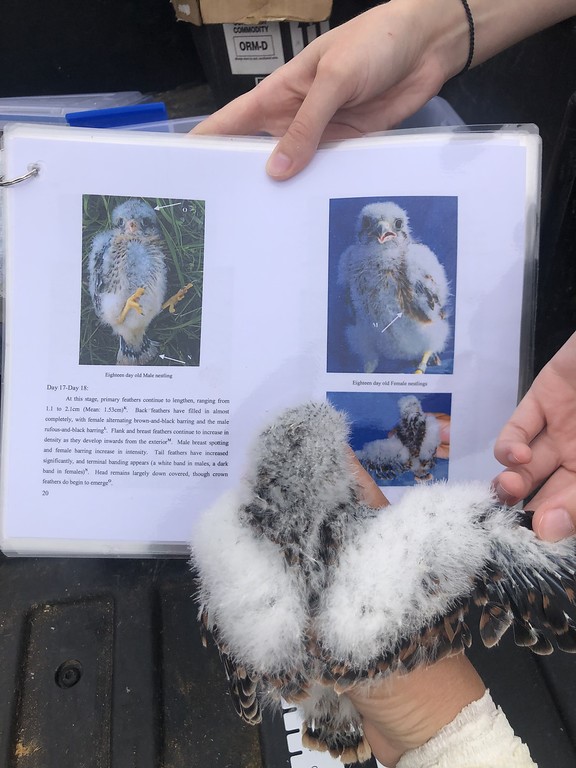

Zoo staff is able to conduct bandings while wearing proper PPE, most importantly masks, since social distancing is not exactly possible when holding a 130-gram bird to take measurements. During bandings, Kestrel adults and chicks are given numbered, aluminum leg bands. These numbered bands help researchers identify individual birds. By being able to identify individuals, researchers can track birds’ lifespan and other data when they are recaptured in the future.

Each aluminum band is fitted to a bird’s leg and provides important information about survival rates, dispersal, and migration, and age should a banded bird ever “recaptured” in the future. Recapture rates on American Kestrels are very low, unfortunately, with only about 2-3% of all Kestrels that have been banded being re-sighted or recaptured again. As a comparison, Canada Geese have a recapture rate of over 20%. The low recapture rate is is another hurdle American Kestrel researchers have to overcome in trying to determine the causes of decline for this species. Without recovering leg band data, it is very challenging to begin to understand a cause for their population declines.

There is very low nest box occupancy in the Brandywine Zoo study area, and missing a season of banding, even with a pandemic, was not an option the zoo wanted to consider. We want to say a huge “thank you” to the landowners who allow research to continue on their lands, and to the team of amazing volunteers who help monitor nest boxes from March through June. Without all their support this project would not be possible. The Brandywine Zoo is committed to wildlife conservation, even in a pandemic, and will continue to band birds, take samples and measurements, and conduct important fieldwork so that a cause, and eventual solution, to the Kestrel’s decline can one day be found.