May 4, 2020

By: Jake Miller, Educator at Fort Delaware State Park

Pea Patch Island is the island where Fort Delaware sits. Legend has it that Pea Patch Island got its name from a shipping accident. Sometime in the mid-1700s, when the island was little more than a sandbar, a ship carrying a cargo of peas became grounded on the shoal. To lighten the load and get free, the ship’s crew off-loaded the peas. These took root and sprouted, and the island formed from silt and sand collecting around the plants.

Whether or not the legend is true, the island was first pointed out to the US government by French military engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant in 1794. L’Enfant had been hired by the government to make suggestions for how the young nation could improve its coastal defense preparedness. He quickly recognized Pea Patch’s potential as a site that could control the navigable Delaware River.

Fort Delaware today, as seen from the east.

The US government did not immediately act on L’Enfant’s suggestion. It was not until 1813 that they sought and received a cession from the state of Delaware for ownership of the island, and they did not begin construction of a permanent fort on Pea Patch until 1819.

There were problems immediately. The surface of Pea Patch Island was extremely marshy, and it was difficult for engineers to find a suitable foundation to build upon. As soon as the star-shaped fort was completed, the foundation began to sink. Before the Army Corps of Engineers could figure out what to do to address these concerns, the fort went out in a blaze of glory (or, at least, a blaze).

Star Fort that burned down in 1831.

In February of 1831, Lieutenant Stephen Tuttle, stationed at the fort, had a fire going in the woodstove in his quarters. Somehow, the stovepipe came detached from its exhaust hole and leaned up against the wooden wall of the room. The resulting fire soon spread to the rest of the fort. Brevet Major Benjamin Pierce, the commandant of the fort and brother of future president Franklin Pierce, had recently lost his wife. The story goes that he gallantly charged back into the burning structure to save her coffin and body. The fort, however, was a complete loss. The men of the garrison, now without shelter on the island, walked to Delaware City across the frozen Delaware River.

Portrait of Benjamin Kendrick Pierce painted for his 1817 wedding.

In 1836, the Army began construction of another fort on Pea Patch Island. Captain Richard Delafield designed this structure, which was planned to be even larger than the previous star fort, with a medieval-style look and a portcullis. Some digging had been done for the foundation, but before any real structural work could be completed, a US Marshal showed up and kicked the Army Corps of Engineers off the island on the grounds that they did not own it.

The US Government claim to the island was based on that of the state of Delaware, but it turns out New Jersey also laid claim to the island. That state had granted rights to Pea Patch Island to Dr. Henry Gale, of New York, for use as a private hunting ground. Gale had offered to sell the island to the government for $17,000 in 1831, but US officials convinced their claim was strong enough to stand on, had not taken him up on his offer. Gale’s heirs had sued the government before the New Jersey Supreme Court, which had upheld their claim to the island.

A letter from Secretary of War John Eaton to President Andrew Jackson regarding the title to Pea Patch Island.

The resulting legal battle over the ownership of the island lasted for a decade. The case was finally brought before a neutral arbiter, Judge John Sergeant of Pennsylvania, who upheld the Delaware claim to the island, and by extension, the US Government claim.

Upon return to Pea Patch Island, Army Corps officials decided that the planned Delafield fort was far too big to successfully complete. In light of the environmental challenges, something a bit more modest was in order. Joseph Totten, one of the premier American military engineers of the 19th century, laid plans for a smaller stone and brick structure, which would eventually become the Fort Delaware which still stands today. Brevet Major John Sanders would be responsible for completing the actual work on the fort and would add his own changes to the design for the sake of practicality.

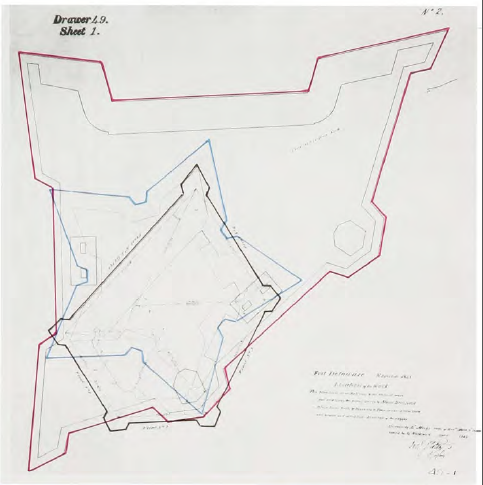

The star fort, the proposed 1836 fort, and the final Fort Delaware all superimposed over each other. The current fort is the smallest.

Several engineers who would later rise to prominence worked on the fort before their names were common. Henry Halleck, eventually general-in-chief of Union forces in 1862 and 1863, helped Totten with the design. Montgomery Meigs, who would become the efficient Quartermaster-General of the Union during the Civil War, was involved in the design, as well. George McClellan served as an engineer during Fort Delaware’s construction phase long before he took command of the Army of the Potomac.

Fort Delaware took eleven years to build, starting in 1848. In order to create a firm foundation for the fort, Sanders flooded the island, then drove piles at regular intervals deep into the mud, sometimes one on top of the other. Once he hit a firm foundation for each pile, he built a deck on top of these for his secure building surface. This would prove to be an immensely stable foundation upon which to build. Sanders’ fort had none of the problems with shifting that the prior star fort had had.

The pile driving operation at Fort Delaware.

The basic building block of Fort Delaware, and other forts of the period, is a casemate. This consists of an arched area made of bricks, with space inside for a cannon. These can be stacked one on the other. The curved arch provides enough structural strength to hold the weight of the next floor above.

Casemate at Fort Delaware

A moat surrounds the fort, with a causeway crossing at the entrance. This provided a single point of entry in the case of attack, a chokepoint which could be held by a small number of defenders against a larger attacking force. The moat is also connected to the river via a sluice gate, which could be raised or lowered to control the water level. As the island is so low-lying, this sluice gate also would have allowed for the island to be flooded over in the event of an attack. Wading through waist-deep water with your black powder weapon is not the best way to start an invasion!

The entrance of Fort Delaware. Photo by @jonathanlukawski

Totten and Sanders also considered the need to be able to withstand a siege. The plans called for a sophisticated water supply system. Rainwater would be collected on the ramparts, filtered in special rooms designed for the purpose, and stored in cisterns built under the floors of the fort. These cisterns could store up to 550,000 gallons of drinking water. Pumps in the kitchen could bring the water up from the cistern, and certain access points would allow engineers to get into the cisterns for repair work.

A cistern cover at Fort Delaware

The fort also featured a new technological development: flushing toilets! These indoor privies would flush into the moat. The theory was that the tidal action of the river would then flush out the moat periodically (how well this worked in practice is not certain).

A restored “privy” (flushing toilet) at Fort Delaware. Note that it is a two-seater.

The story of Fort Delaware’s construction is a story of human resourcefulness, creativity, and determination in the face of long odds. The fort still stands as a monument, at least in part, to the brilliant men who designed and built it.

Present-day Fort Delaware. Photo by DE State Parks Volunteer Photographer Becca Mathias